It’s been one of those weeks at work, the kind where time moves back and forth in an odd dance in the mind, making it feel like minutes are hours and hours, minutes.

It’s been one of those weeks at work, the kind where time moves back and forth in an odd dance in the mind, making it feel like minutes are hours and hours, minutes.

Deadlines, chaos, and nerves–there’s something big to work on, and when the sun meets the horizon (at this time of the year, a reminder that you’ve been at work far too long–especially when you watched the sun rise above the horizon on the way in), you crave company that won’t talk about work and maybe even something to speed along forcing the tension of the day from your shoulders to fall and gather like dust with others’ tensions on the floor of a bar or quiet living room.

Conversation and a cocktail; it doesn’t get much better than that!

The Power of a Drink

“First we must understand what, functionally, a cocktail is. I will inquire into no man’s reasons for taking a drink at any hour except 6:00 p.m. They are his affair and he has a rich variety of liquors to choose from according to his whim or need: may they reward him according to his deserts and well beyond. But when evening quickens in the street, comes a pause in the day’s occupation that is known as the cocktail hour. It marks the lifeward turn.”

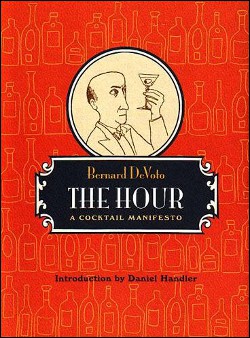

– Bernard DeVoto, from The Hour.

I love a good cocktail. (Personal preference: the martini.)

It is not that I want to lose myself in spirits, but rather–celebrate all that mankind has wrought in a perfect cocktail glass glistening with condensation and filled with gin, vermouth, and lemon oil swimming on the surface. One can argue that a dash of orange bitters belongs in or fouls the drink; I’m fine with either.

I’m also fine with olives.

Bernard DeVoto was not fine with olives in a martini.

“Who?” you probably ask.

DeVoto was a professor turned writer, known for writing about history and literary criticism (he was not afraid to try cutting through the bone with his opinions).

And yes, he even wrote about cocktails…

The Book

Bernard DeVoto’s The Hour: A Cocktail Manifesto (affiliate link) was the first book I read this year. Of those who prefer olives in their martinis, he said:

“And, I suppose, nothing can be done with people who put olives in martinis, presumably because in some desolate childhood hour someone refused them a dill pickle and so they go through life lusting for the taste of brine.”

Followed by this:

“Something can be done with people who put pickled onions in: strangulation seems best.”

Do not take DeVoto as an authority on the martini; read him and appreciate a time when we put so much effort into everything we wrote. (The book was written in the late 50s.) Whether you agree with him or not, it’s hard not to appreciate the way the curmudgeon put words together. I’m sure the originators of many classic drinks (including the martini) would scoff at DeVoto’s arrogance and call him out on his inaccuracies, but that’s not the point.

He’s really damn funny!

The Evils of Rum…and the Enemy

“We are a pious people but a proud one too, aware of a noble lineage and a great inheritance. Let us candidly admit that there are shameful blemishes on the American past, of which by far the worst is rum.”

DeVoto has a flair for asserting his opinion in ways you can’t help but appreciate, whether you agree with him or not.

I’ll say it right here: I know very little about rum. I can’t recommend an aged rum worthy of pouring into a glass and sipping straight, like scotch or whiskey. In general, the rums I’ve had (even some more expensive rums) have left me flat. They have only been worthy of mixing–not savoring on their own. (If you have a recommendation of a good sipping rum, I’d love to hear it.)

Still, I wouldn’t say rum is the biggest blemish on the American past…and neither is DeVoto. Remember, while he started out an English professor, he moved on to writing about history and knows many of the true blemishes on the country’s past.

Reading The Hour was a reminder that many no longer appreciate–or even recognize–great satire and sarcasm.

Were a writer to say today that rum is the worst thing to happen to the country, instead of readers appreciating the ridiculous humor, many people would be outraged…perhaps even writing to publishers calling for the writer to never be published by them again.

Those people could do well with a fine drink to calm them down.

No drink (save the martini and whiskey) are spared in DeVoto’s The Hour. Cookbooks aren’t even spared:

“I’m talking about cookbooks. Every publishing house has from three to a dozen of them and they are money in the bank. Soon or late, usually not very late, this season’s novel about the bitch with the compassionate heart in rural Georgia or the court of Louis XV stops selling. A cookbook never does. In season or out, fat years or lean, it is the mainstay of the publishing business. The grandchildren of the author, who lived in an era when recipes began “take four pounds of butter and four dozen eggs,” set up trust funds for their grandchildren and the publisher loves them more warmly than the novelist who makes Book-of-the-Month Club every time. I don’t know how many cookbooks are sold, but it must be upwards of a million copies a year. Every copy has enough virus in it to infect a city of fifty thousand; every copy is a recruiting office for the enemy.”

Who (or what) is the enemy?

Pretty much everything except martinis and whiskey; all the drinks created to bulk up the “Beverages” section of cookbooks.

I’ll spare the details, but of these drink recipes, DeVoto says:

“Merely to read the formulas paralyzes the stomach muscles for as much as twenty minutes and a single sip would send the iron dog of the epoch they originated in galloping toward the nearest fire hydrant.”

Some other gems:

“Throw away that bottle of grenadine. Never buy another one.”

“Cheap liquor is grudge liquor.”

“Don’t have much to do with people who drink sherry at any time except with soup; there’s something wrong with them.”

“Orange bitters make a good astringent for the face. Never put them in anything that is to be drunk.”

“Let’s be clear about this: no Manhattans or rum.”

“Remember always that the three abominations are: (1) rum, (2) any other sweet drink, and (3) any mixed drink except one made of gin and dry vermouth in the ration that I have given.”

I don’t dare tell you what DeVoto thinks about punches and those who make and drink them.

The Martini

It’s probably clear by now that DeVoto was a big fan of the martini. I’ll let his words carry his feelings about the drink:

“The proper union of gin and vermouth is a great and sudden glory; it is one of the happiest marriages on earth and one of the shortest-lived. The fragile tie of ecstasy is broken in a few minutes, and thereafter there can be no remarriage.”

And remember, the martini should only be taken during “The Hour.”

The Hour

So why have I devoted so much time to a review about a tiny book that’s really just a curmudgeon’s celebration of the martini?

Because the final chapter of The Hour is one of the most soothing things I’ve read in years.

Imagine that stressful week at work, when all that can go wrong does go wrong. You’ve worked late; the sun has slipped behind the horizon and you rush through the city to find camaraderie and something to take the edge off a rough week.

It’s not that you want to lose yourself in the bottom of a glass; you just want to go from the stress of a busy week at work and lose yourself in a world where everybody knows your name. (Or where you can, at the very least, relax and discuss things that really matter–things beyond the toil of the days–with people who appreciate time away from work as much as you.)

Can you hear your body settling into the over-sized chair and smell the distant whiff of juniper and lemon oil?

The last chapter of DeVoto’s The Hour is like having that second martini after a long week of work. With words, DeVoto does in one small chapter what took distillers hundreds of years to do with their craft.

Gone is the sarcasm. DeVoto talks about drinking in clubs he’s frequented for so long that “my friends’ grandchildren stand up and offer me their chairs.”

He celebrates the hour as a time not be locked away in clubs with stuffy men talking business, but taking drinks in the company of smart women. (I found this attitude interesting given the time the book was written, a time when women were still seen more as cute objects than equals. DeVoto goes as far as saying that if you can’t have a martini in the company of a smart woman whom you adore, a martini isn’t worth having.)

He also writes:

“So it is a good place to reach just ahead of the pursuing feet. Tiptoeing across the almost dark cavern of the lounge (at the hour all lamps should be shaded and only a few of them lit, for if the body is in shadow the soul will the sooner turn toward the sun), I take my drink to a chair so big that one’s head cannot be seen above it’s back, by a window that faces a cross-town street. We are near enough the avenue to hear the traffic diminishing. This is the hour of diminishing, of slowing down, of quieting. Thus islanded in dimness and the murmur of traffic fading toward silence, one is apt for the ministration. Calm against background tumult is an essential of the hour; it is the firelight shining through the cabin window on the snow of the forest, the strong shack beside a lake whose waters a gale is hurling up the shore.”

Leave a Reply