I’ve mentioned many times that artists inspire the way I look at writing as much as other writers. One of my favorite art blogs is Muddy Colors, where I’ll stop what I’m doing in the morning to read whatever Greg Ruth writes about and shares.

I’ve mentioned many times that artists inspire the way I look at writing as much as other writers. One of my favorite art blogs is Muddy Colors, where I’ll stop what I’m doing in the morning to read whatever Greg Ruth writes about and shares.

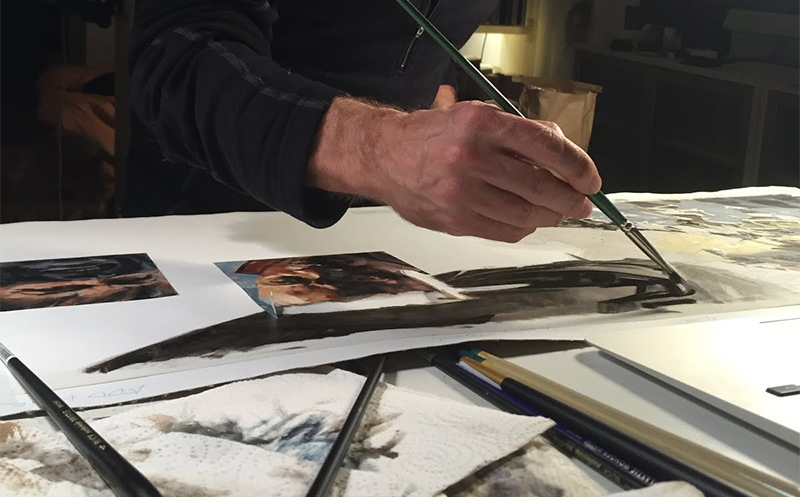

Maybe there’s something in a name, because another favorite contributor to the site is Greg Manchess.

Sometimes I Start and Stop

Several weeks ago, I started an entry based on Manchess’ post, Things I Learned From Creating 122 Paintings in 11 Months. (That’s a stout painting schedule to be sure!) Unfortunately, I had to log into work, so I stopped the entry and didn’t get back to it at lunch. And then I didn’t get back to it for days. But here are some of the parts I loved about the entry:

Sometimes, when the vision is clear and the means are not, we have to make difficult decisions. What do I sacrifice? How badly will I fail? Can I survive?

As a writer, I can always see what I want in my mind…but sometimes getting it down as I imagine it is a problem. If I’m writing something more serious, it requires deeper attention. If I’m busy at work or not as willing to cut myself off from friends and family as I lose myself in a section of a story, I know the section will not be all it should be.

Similar questions Manchess poses arise: Do I just do it anyway, or do I work on something more clear until there’s time for complete attention? Do I take a day or two off work, or do I go into it when I can, knowing it won’t be all it should be and fix it later? The important thing is to keep moving — even if it’s like Manchess jumping to another painting.

I basically wrote a three hundred page novel, learning my characters and their backstories, and finding what scenes to keep and what to let go. Then I severely cut the whole thing down to about 30K words.

Revision is where good novels become great. While I’d love to work from a tight outline, I’m one of those writers who just gets it out there and then decides what stays or goes. I’ve removed entire storylines with characters I’ve loved from novels. That act of discovery and putting it all down allows me to see what to keep and what to release.

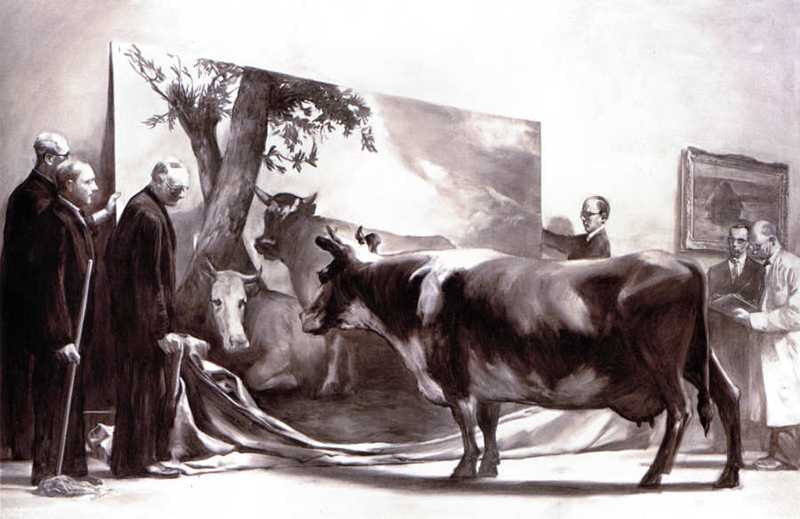

I finally learned that getting it right means making it believable, not actual.

My wife is an artist. While her roots in comic book art mean she mostly draws from her head, sometimes she works from photo references. And sometimes what a photo shows wholly accurate…just looks weird. Like, “Oh, the anatomy on that is wrong!” even though it’s not — it’s captured from life.

But in those moments she goes with what’s believable to the eye and the mind — not what the reference showed.

As a writer, there are often progressions, dialogue, and many other technically accurate things that seem stilted. Sometimes characters have to do big things that may not be accurate, but damn-well better be believable, even if one is writing a story in which a character flies.

Even superhero stories establish world rules…and to break those rules makes the willing suspension of disbelief crumble.

At seventy-five paintings in, I started to doubt.

One thing I’ve always envied about artists is how they can hold up a work and BOOM! you know instantly if you like it or not. Physically, if I hold up a terrible manuscript to a great work, they look the same. At the same time, when discussing this concept with an old [artist] friend, she brought up a good point that went something like, “Yes, but imagine walking into a museum and instantly seeing hundreds of pieces reminding you how you’re not as good as you thought.”

We all have our doubts. I’m a confident writer who doesn’t experience the doubt in their work many writers seem to carry, but even I look back over things and think, “I thought this was great, but it can be better…”

Being 75 pages into a manuscript and having doubts is bad enough…I can only imagine what it’s like to doubt yourself 75 paintings into a project. (It’s much easier to revise text than paintings.)

Facing the Void

Manchess’ 9th point in his entry about creating so many paintings in 11 months is a great section. I’d say, “Just go read it all,” but I understand not leaping to every link in an entry, so…the parts that really hit me:

…each attempt to create something like a painting is met with some form of doubt or insecurity, and one way to shield oneself from insecurity is to train and paint so much that we overwhelm the question. To understand our material so well the questions never arise.

As a writer, it’s why I think always working on something (or even several things) is important. The people who don’t seem to finish are those focused on a singular thing here and there who have more time to doubt their abilities than hone them. In the act of regularly creating, confidence reveals itself.

But the real conflicts with any vision must be faced down with confidence in skills you’ve learned, enthusiasm that borders on the immature, and only sharing your strife with trusted individuals that know how to help you maintain your stamina. Friends.

I love the line about enthusiasm. I still write sections of novels and complete short stories that are so much fun that I’ve jumped up from my chair, pointed at the screen, and yelled, “Fuck yeah!” Immature, sure, but it never hurts when a morning’s writing reminds you of how you felt when you first began taking writing seriously.

I also like the line about sharing strife with trusted individuals. Social media and other Webby things makes it so easy to complain. We can read a work we don’t like and fume about it…but really, what good is that? And why complain about something you love all the time — especially out in the open?

While I share a lot, here, I will never knock other writers because I’d rather use this space to support writers I love. But trust me, I’ve been known to fume about books that I felt were lacking that it seemed the rest of the world loved. And those moments of strife and doubt (not so much in my abilities, but my constant struggle with, “This is what I love more than anything, and it’s not what I do full time,” is something that occasionally pops up here, but the deeper aspects of that struggle are reserved only for a few individuals.

And the last lines of this particular Manchess piece:

Fatigue, fear, doubt is simply part of the process. It takes a lot.

But then, so what?

I think that “But then, so what?” is important. The reality is if you’re lucky to see a novel released into the wild, it’s a flicker. It is soon forgotten by releases by other writers weeks, months, and years later. To us, it feels like everything, but sadly, most of the world won’t care about your best efforts.

That’s why learning to love the work simply for the sake of doing it matters so much. It’s possible that’s all you’ll get if you look at it that way, but if you realize how much you grow with each new work (and what those efforts may lead to down the line), that’s hard to put a price on.

A Few Things About Painting Problems

I won’t dissect Manchess’ most-recent Muddy Colors post, but it’s worth reading with an eye toward writing. Like a painting, a well-written novel or short story has layers and structure, and if you feel something is lacking in what you’re writing, it’s probably because some aspect of the following is off:

Value and Shape: There’s a familiarity even in most avant garde writing — and definitely certain expectations in more traditional formats. Stories have a shape, and it’s important to keep your hands on it like a sculptor to ensure nothing becomes lopsided and flies off the wheel.

Silhouette: Complexity can be nice, but it’s nice to consider what your story looks like from a distance. (I know that sounds weird, but even if it’s, “I want my story to feel like this kind of landscape,” keeping the silhouette of that space in your mind doesn’t hurt things.)

Contrast: When I write early drafts, characters may not necessarily all sound the same, but they don’t sound as different as they should. It’s only in later drafts that I do a pass to make sure any needed contrast is clear to readers.

Edges: As a writer, this is similar to contrast for me, but differs in that I see the edges of a story as the layers. It’s important to bring certain things forward with bold edges, while letting soft edges sit behind things, making the world seem full and real. (If you want to see some neat art, check out Manchess’ 10 Things about Edges entry.)

Color: Color can be garish, but it can also be the thing that brings a work together. It can make all the other elements of a story unified when done well. Like many writers, when I first started writing, I tried too hard. While I avoided excessive adjectives and other common mistakes new writers make, I wanted my prose to rise off the page and be recognized as a beautiful thing on its own. Looking back at some early work, it was the literary equivalent of a paint factory exploding!

The world of art is full of stunning monochrome works…some completely black and white, and others incorporating just a bit of color. Many cinematographers and photographers still look at the world in black and white before letting the color in.

If there’s one thing I know about my own writing process, it’s that I can always add color later. I can allow myself to write something sloppy on my lunch break at work (instead of nothing at all), knowing it will eventually come to life with every element working together.

Leave a Reply