Fly Me to the Moon is a short story about a homeless man who is convinced he can communicate with the ghosts he believes to live on the moon…if only he can fix a broken radio found in a dumpster.

Fly Me to the Moon was written during a Person, Place, Thing writing challenge.

* * *

This work is released under a Creative Commons license. You are free to copy, share, and transmit this work, but please credit Christopher Gronlund. Do not use this story for commercial purposes without the author’s consent.

For more information, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-?nc-?nd/3.0/us/.

For more information about Christopher Gronlund, visit his Web site.

* * *

Fly Me to the Moon: HTML (Below) | PDF | EPUB

* * *

FLY ME TO THE MOON

by Christopher Gronlund

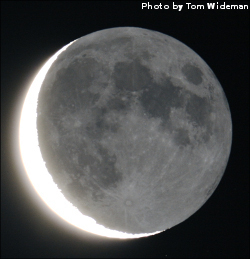

Mad Man Morgan thinks the moon is full of ghosts, all the people he ever knew—all the people everyone ever knew—dancing on the surface, shining down upon us all. When the moon is full he stands before Saint Louis Cathedral shouting, “Look up!!! Don’t you see them?!” He repels the passing crowds like opposing magnets; they give wide berth and continue toward the bars and clubs near Bourbon Street, maybe complaining about the city’s “homeless problem” on their way.

One night he shouts at the crowds and someone listens, a nineteen-year-old from Baton Rouge armed with a fake ID and a thirst for the closest thing to genuine absinthe she can find. She reeks of patchouli, and while she is more comfortable casting spells in the safety of her dorm room at LSU, she feels “at home” in New Orleans and visits whenever she can. She believes she’s connected to things on a different level somehow, but it’s little more than youthful naivety, and she will abandon all she believes in during her late twenties when she’s offered a “career” in California. But tonight she wants to listen—she stops and looks up at the sky with Mad Man Morgan.

“I don’t see them,” she says. “What are you looking at?” She closes her eyes and tries “tuning in.” She tries “connecting” so she can understand Morgan like nobody else ever has before.

He points to the moon with dirty fingers and yells, “Up there! They’re everywhere! Can’t you see them all glowing?”

She looks hard, wanting to see whatever it is Mad Man Morgan sees, but the only thing above is a swollen moon, and she feels guilty for coming down to the city in search of booze and forced mood instead of studying for an exam she has on Monday.

“I’m sorry, I don’t see them,” she says, her patience waning. She wants to leave—this isn’t as much fun as she thought it would be. There’s something wrong with this man, something deep inside that makes her sad. Maybe she really does have a knack for connecting. She gives him a five dollar bill to stave off some guilt and, like so many others, makes her way toward Bourbon Street.

She doesn’t turn back to look at him as she goes. She doesn’t hear him whisper, “Can’t you see them? Can’t you see my wife?”

* * *

“Whaddya think?” Mad Man Morgan says to a fat pigeon eating a piece of sourdough bread from a muffuletta. Morgan has a broken radio and an idea. “Do you think it’ll work?”

He found the radio in a dumpster behind a nice little tourist trap of a restaurant. Fat pigeons and mad homeless men don’t mind tourists; if they had their way, every place in town would be swarming with out-of-town visitors. Morgan may be mad, but he knows that where there is food and tourists, there is waste, and pigeons aren’t the only creatures in the area sustained by the hard ends of broken sandwiches.

Mad Man Morgan believes if he can only fix the radio, that he can talk to the ghosts on the moon. He believes if he can fix the radio, for the first time in ten years, he’ll be able to talk to his wife.

* * *

Mad Man Morgan used to fix brains. With years of study at Tulane and the steadiest hands in Orleans Parish, if Humpty Dumpty fell off a wall—as long as he only broke his crown—Morgan Duchesne, M.D. could put him back together again.

Morgan had everything: the job, the house, the cars, and most of all, a lovely wife. They vacationed on private islands, attended formal parties at the mansions of powerful politicians, and dined in the finest restaurants, the kinds some rube visiting from Milwaukee wouldn’t find in any tourist guide. Life couldn’t be more perfect. They lived a fairy tale until the year something grabbed his wife and refused to let go.

He watched her disappear, slowly at first when the first tumor appeared, and then faster as more arrived. Rogue cells that worked her over like a vicious gang, getting a finger hold and then ripping and ripping and ripping until there was nothing left to tear apart. Morgan and his colleagues—all the king’s horses and all the king’s men of the neurosurgery set—couldn’t put Morgan’s wife back together again.

When Morgan’s brain went on vacation, it wasn’t the result of tumors; he simply went mad, abandoning everything he once had. Refusing all help, he disappeared to the streets of the city. Those who once knew him now look the other way when he stands in the street yelling at the moon.

* * *

This is how Mad Man Morgan sees it: when someone dies, their body sits beneath the ground, or maybe cremated and returned to the earth or placed on a shelf, thinking about their life until the full moon comes around. Those who need more time to think die during the waning moon, giving them plenty of time with their thoughts. Those who had it together are taken closer to the full moon

. The evening his wife died, the moon hung heavy and bright in the sky, seemingly as large as an apple, even at its apex.

When the moon is full Morgan believes “The Upload” occurs—millions of souls ascending to join those who walked before, to dance and live in harmony on its glowing surface.

He believes he will join them, someday.

Someday he’ll dance with his wife again.

* * *

He has a broken radio, but no tools and only the advice of a fat pigeon more interested in looking for crumbs than offering suggestions.

“I see how it is,” he says to the bird. “You’re no better than those damn grackles! It’s spooky the way those things look at ya, not all dumb and stupid like you.” The pigeon cocks its head, as though trying to comprehend Morgan’s words and figure out if it had really just been insulted by a dirty man who smells like armpits and the Mississippi River.

“It’s like they know something, but they won’t let go of that knowledge. Damn greedy grackles.”

He takes the radio and sets off to find some tools, but all he finds in dumpsters anymore are papers, sour food, and the occasional broken appliance.

“Doesn’t anybody throw away anything good anymore?” he says to neither human nor bird. He’s not even talking to himself—simply speaking for the sake of doing something. Talking, even to himself, is comforting. He doesn’t feel as alone when he speaks.

“Tools. Where can I find some tools?”

* * *

Thomas Patterson builds things. A high school dropout, he’s good with a drill and swings a mean hammer. He has great balance and no fear of heights. He hates his boss, though, and he hates his job framing houses, apartments, and strip malls. Sometimes, like today, he does restoration gigs, making sure old New Orleans doesn’t fall apart into a pile of old wood, bricks, and mortar.

Morgan waits until Thomas is eating lunch with his “colleagues.” A memory flashes in Morgan’s brain like a tiny lightning strike: he used to eat lunch with “colleagues” too, but now his only company is madness and flocks of dirty birds that refuse to accept him as one of their own. Morgan waits until the crew’s attention is focused more on bologna sandwiches and greasy potato chips, than their tool belts, drills, and hammers. As quick as a memory, Morgan is running down the street, carrying a drill, a yellow plastic case, and a hammer. He doesn’t look back.

He doesn’t know how long he’s been running—he doesn’t concern himself with things like that. The only clock he follows is the moon, and he knows the lines of communication will open wide tonight during the Upload. If he can fix his radio, he can talk to his wife.

* * *

It’s getting dark and Mad Man Morgan hasn’t had any luck. His counsel of wings has flown off to the safety of treetops for the night, and even after using the screwdriver bit for the drill he found in the yellow case to carefully open the radio like a black plastic skull, he’s not getting a signal.

“Juice, I need juice!” he mumbles.

He knows where he can find an outlet, a place to plug the radio in…behind a restaurant skirting the square.

“Town’s nothing but eateries throwing away wrappers and spoons, dammit!” Mad Man Morgan gets edgy when he’s in a hurry. Soon the moon will rise; soon he will talk to his wife and maybe remember more about who he really is. Maybe he’ll even “get it all back,” if he can only remember what it is he lost in the first place. His wife will tell him—he’s sure.

The dumpsters are clear of others like him; they come out later, after the restaurants have closed, searching for a free meal. The coast is clear and he plugs in just in time for the moon’s climb through the sticky night sky.

All he gets on the radio are hisses and pops. He sways back and forth, like he’s sitting in an invisible rocking chair.

“It’s just not high enough. Just not ready, is all.”

He misses the comfort of the birds. He’d even welcome a grackle right now.

He spends the evening trying to tune in to the moon, interrupted here and there by kitchen workers emptying garbage. He unplugs and retreats to the shadows when the back door swings open; then, when they are gone, he plugs back in, hoping to find the frequency for his wife.

“Can you hear me, honey? Claire, can you hear me?”

But the night only whispers static.

* * *

Mad Man Morgan still knows a thing or two about brains. He remembers a long surgery, working on an epileptic. He and his colleagues knew if they could only find the part of the brain that wasn’t used for anything more than making the body convulse and cut it out, there was hope the patient could live a normal life. Primitive ideas seemed to work with the brain. If it takes a beating, drill a hole in the head and drain the fluid to ease the swelling. If a part of it acts up, simply find that part and cut it out. If something grows that shouldn’t be there, cut it out and hope for the best.

The best didn’t happen with his wife, but Morgan helped give an eighteen-year-old a promising future by simply removing the part of the brain that brought about seizures. They woke the patient after exposing his brain to their prodding fingers, and then they mapped it. They asked the patient simple questions and stimulated parts of his brain with an electrode. They asked him what his favorite color was, touched a part of his brain, and he said “Cat!” They touched parts that made him move his fingers and toes and they touched parts that made his tongue tingle. They made him talk and twitch, a group of puppet masters with their prized marionette.

* * *

Mad Man Morgan mapped brains and knew how to make them work. He also knew how to make them stop.

He unplugs the radio and plugs in the drill. It hurts at first. For some weird reason he remembers a news story about a man in prison who removed his testicles with a spoon because he was “bored,” and the pain stops. The noise from the drill is barely heard over the sounds of the busy kitchen, but it echoes like a jackhammer in his head. Morgan knows he doesn’t have much time—the moon only calls once a month.

He pulls another drill bit from the case, the longest one. It glows in the moonlight like a slender a key. He takes it in his left hand, picks up the hammer in his right and drives the drill bit through everything that matters.

His last thought is of his wife.

* * *

Bryan and Stuart argue about whose turn it is to take out the garbage from the kitchen, so their boss tells them both to do it. They open the back door to the restaurant and both see different things.

“Holy shit!” Bryan says, not sure if he should be sick, or curiously fascinated by the man on the pavement with the drill bit sticking out from his forehead. “Isn’t that that crazy guy who’s always talking to birds?”

But Stuart doesn’t hear; he’s looking toward the sky and saying, “Hey, did ya see that? I think a shooting star just hit the moon!”